C2V April Notes From The Trenches

Welcome friends!

Well, that escalated quickly. We had a nice venture recovery going here, particularly in exit markets, where M&A and PE buyouts had been steadily gaining steam for a couple of quarters, with venture-backed IPOs recently joining the party as well, and while the Q1 numbers show more of the same… we now find ourselves engulfed in some light economic chaos so as far as what the future looks like, well, who knows.

So, while we’d much rather be contemplating more fun questions like, “Given this liquidity thaw after a multi-year deep freeze, will our next exit result in the two of us collapsing in a puddle of tears like Rory on hole-19 at Augusta a few weeks ago?”, we felt like it would be irresponsible of us not to delve into what’s going on in the economy as a whole and where that might leave those of us in ventureland.

Quick caveat – we have long adhered to a “no politics” rule in our newsletters (plenty of places to find that in other print and West Coast VC podcasting realms), and this newsletter is no different.

In other words, the discussion that follows is not political commentary. We are not attempting to make an argument for any political party, nor any candidate (frankly, we’re increasingly frustrated with all of them these days). Additionally, nothing we say here is in any way meant to be a personal affront to anyone, so we’d respectfully request that you please try not to take it as such.

Okay, enough hedging, we’ve done all we can do here. Let’s get into the discussion…

Trade, Tariffs & Prosperity

We’ll get into why protectionism is not, nor ever has been, the right path to prosperity, but first, a look at the rationale for doing this in the first place.

Why Do We Need This?

Short answer, we don’t. At least not to anywhere near this degree. The “bring manufacturing back” line as a campaign tool is not remotely new. It’s been such a staple of American campaign platforms for so long that we wouldn’t be surprised if half of our elected officials had it tattooed somewhere on their bodies.

That said, the general sentiment is a fallacy in and of itself, and a dangerous one at that. For something to be brought back, it must have been absent in the first place, or at the very least, in persistent decline. This is simply not the case for American manufacturing, now or really at any point in the past 100+ years.

Of course, there are always improvements that can be made, but when you’re starting in as a good a position as we are in the U.S., completely upending the system rather than making targeted improvements on the margins (i.e., using a sledgehammer instead of scalpel) risks doing far more harm than good (and unfortunately, that’s what appears to be playing out right now).

As for that starting point…

1) We have consistently grown our manufacturing base for 150 years and counting

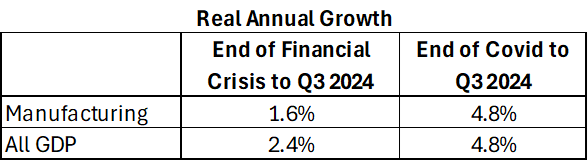

Other than in recessions (when manufacturing declines along with everything else), US manufacturing output has grown every single year without fail, including at a 4.8% annual rate since the end of the Covid recession (the same as GDP overall), a pace that every developed nation on earth (and quite a few emerging ones) would be delighted with.

2) We’re the second-largest overall manufacturer in the world and the most efficient by a mile

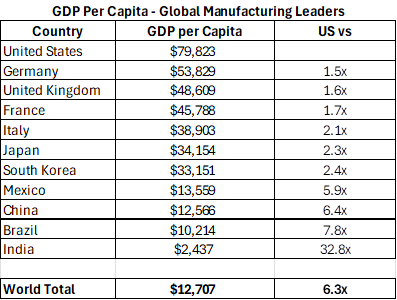

While China leads in total manufacturing output (by just under 2x the U.S.), the U.S. manufacturing sector is almost 7.5 times more efficient than China’s, and 1.5 times more efficient than the next closest nation, a testament to both the sophistication of the goods we produce and our relentless commitment to innovation.

In fact, we are so far ahead of the rest of the world in manufacturing efficiency that the gap between the US and the number two country on this list is almost twice as wide as the gap between number two and number seven.

It is also important to remember that manufacturing is just one component of a developed economy in 2025, and relative to these same global manufacturing leaders, we are equally dominant in overall wealth per citizen.

3) Are trade deficits even a problem?

As far as the US running a net trade deficit overall, economists are divided on whether it is immaterial or detrimental. Still, as far as balancing trade with every individual country, you will not find support from a single credible economist, and with good reason.

Let’s look at Vietnam as an example. We run a $123.5 billion trade deficit in goods with Vietnam, our fourth-largest trading partner. Does this mean we’re “losing” to Vietnam? Leaving aside that you’d be hard pressed to find many Americans who would trade their non-manufacturing job for a one-way ticket to Vietnam to work in a sneaker factory, short of stopping nearly all purchases of goods from Vietnam, balancing trade with a country where the average household makes $2,500 – 3,000 a year (~1/40th of the US) is just not possible (can we realistically expect the average Vietnamese family to buy an American car that costs 20-years-worth of their gross income?)

Furthermore, the $123.5 billion of net goods we buy from Vietnam each year is not a permanent condition and if it serves to raise that average household income (as it surely will), trade with Vietnam will start to balance itself with no intervention at all (somewhere Adam Smith is pumping his invisible fist right now).

Our trade history with China is a useful comp here (having 40 years worth of data to work with), but before we do that, a quick note that we are not ignoring the very real facts that a) a wealthier China comes with other material issues (though not ones we should necessarily expect from other emerging markets), and b) they didn’t get here purely through hard work and innovation (there’s also been a fair bit of lying, cheating, and stealing along the way), but as one of our longest-standing emerging market trade partners, it also happens to provide the most robust dataset with which to illustrate this point, so please try to ignore the name and just focus on the data.

From 1985 to 2008, US imports from China grew 87x vs 18x for exports, while China’s GDP per capita grew 15x. As we’ve seen above, China’s GDP per capita remains a small fraction of the US's even today, and in 2008 it was only a third of its current size. But even reaching that meager level of wealth was enough to flip the trend to where the annual percentage growth in US exports to China (on a rolling 10-year basis, to eliminate year-to-year noise) has outpaced the percentage growth in imports every year since.

The result? Since peaking in 2018, our trade deficit with China is down 29%, and last year’s deficit was our lowest since 2011.

Again, we still have a ways to go, this relationship is far from perfect, and we are not defending China’s trade practices here (nor its geopolitical shenanigans), just pointing out that emerging market wealth increasing over time is generally a net positive for US exports and overall balance of trade (and free markets can eventually find a natural equilibrium all on their own).

So, manufacturing in the US is far from dead, nor is it in decline; yet, the idea of a manufacturing rebirth still appears to resonate with many Americans.

Which leads to our next question…

Who Wanted This?

Short answer, almost everyone… and almost no one.

The Cato Institute conducted a survey in July 2024 on globalization, and the results are truly fascinating. We’d encourage everyone to check it out as we’re barely going to scratch the surface here. Still, for our purposes, the most important result is Americans’ response to the following two statements:

1) “America would be better off if more Americans worked in manufacturing than they do today.”

Agree: 80%

2) “I would be better off if I worked in a factory instead of my current field of work.”

Agree: 25%

This is quite a paradox indeed. Whether the average American is aware of just how exceptional we are at making things is hard to know from this (though it seems like many don’t), but it does seem clear that Americans are A) aware that, notwithstanding overall growth, manufacturing jobs have shrunk, both overall (having peaked all the way back in 1979) and as a percentage of the overall workforce, and B) seem to think this is a problem overall.

Yet, very few Americans want a manufacturing job. In fact, given the perpetual problem American manufacturers have filling their open roles, we suspect that even the bulk of that 25% is imagining a manufacturing job that simply doesn’t exist, in any country.

For the most part, the manufacturing jobs that have moved offshore over the years, and those that have proved challenging to fill here, are the dirtiest, dullest, and most dangerous (before you complete that eye-roll, please understand that we’re not suggesting this is true because it’s our core investment thesis, instead it’s our core investment thesis because it is true).

In other words, while much of this offshoring may have initially been driven by profit, those lost jobs have since been replaced with better ones, and almost no one wants to trade back.

As we covered in our prior newsletter, one of the key reasons we are bullish on robotics is that a significant proportion of the roles robots are best suited for are jobs that companies simply cannot fill, and those openings have been on a steady, upward trajectory for 25 years.

Obviously, there’s a fair bit of year-to-year noise and economic cycle impact here, but as you can see, the trend in manufacturing job openings that can’t be filled is only going up over time.

Why is this?

To start with, outside of recessions, the US has been consistently at or above what economists consider “full employment” for decades (essentially the point at which the unemployed are individuals intentionally changing jobs or taking time off to upskill). So, taking a manufacturing job doesn’t mean finding gainful employment; it means trading out of a service industry job, which the average American does not seem to be interested in doing.

But wait, don’t manufacturing jobs pay well? In an absolute sense, yes. Relative to service industry jobs, not really.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the only two service industry job categories that average materially lower weekly incomes than manufacturing are the “retail trade” and “hospitality and leisure” sectors. The rest of the service industry earns the same or more per week as manufacturing workers.

Compounding this is that service industry employees work substantially fewer hours on average. Excluding retail and hospitality jobs, the average service industry employee works 10-11% fewer hours each week, resulting in an average hourly wage that is 23-24% higher.

As for those retail and hospitality workers, they earn about half the weekly income of manufacturing workers, but they work even fewer hours (33% fewer hours per week than manufacturing workers).

Perhaps there are some of these service workers who would prefer higher-paying manufacturing jobs, but on the whole, it seems they prefer the lower hours to higher pay. After all, manufacturing jobs are available, and the US has a relatively efficient labor market. Therefore, if individuals truly desire higher-paying manufacturing jobs, they would likely be working in manufacturing (or the retail and hospitality sectors would be paying more to retain them).

In other words, quality of life is also a significant factor here, which leads to our next point on globalization…

Standard of Living

Of course, the metric that matters most to citizens of any country is standard of living, which is not absolute income levels, but rather income minus cost of living (plus a bunch of externalities, one of which we’ll touch on below), and this is where globalization has benefited Americans arguably more than income growth over the past 80+ years.

Back to that Cato Institute survey, when respondents were asked to choose the three political issues most important to them from a list of sixteen (e.g., economy, taxes, immigration, etc.), the number one response was “Inflation/prices” at 40%. So, if the average American believes that globalization and/or offshoring of manufacturing is bad for the country, it seems safe to say that a few months of tariff-driven price hikes will dispel that notion in short order.

We should touch on one additional externality that (if people knew what they were signing up for) would put an additional, and likely significant, damper on the enthusiasm for more low-end manufacturing jobs.

One major impediment we already have to commercial investment in general (x100 for heavy industry) is the “not in my backyard” phenomenon. This is a cousin to the manufacturing job duality above – even if people want more factories, they want them built in someone else’s neighborhood – and in this case, with a very good reason: pollution.

Manufacturing & Pollution – The Quick and Dirty

(Hey, just because we’re off the economic rails doesn’t mean we can’t still have a little fun with this)

Before anyone decides that we should all aspire to China’s current manufacturing base, we’d strongly encourage them to spend a little time there (and if you’ve been to Beijing on even an average air quality day, you know exactly what we’re talking about). It’s not uncommon to look out your Beijing hotel room window in the morning and not be able to see the buildings across the street through the thick yellowish haze in the air (which may or may not also make the entire city smell like burning diapers).

Not only is this no way to live, it also comes with huge public health costs, and we have enough problems with healthcare cost inflation (incidentally, the number two response on that Cato Institute “most important issues” list), without onshoring a few billion tons of burning diaper smog.

As we noted earlier, none of this is to say that we can’t improve in the realms of both manufacturing and trade, but this is a scalpel problem and big, sweeping import tariffs are very much a sledgehammer solution (honestly, they might be closer to an ICBM solution; in all sorts of ways).

Complexity, Efficiency, Price & Choice

If widely applied tariffs on substantially all imports didn’t work 100 years ago, they have no chance whatsoever today. Over that period, the global supply chain has become immensely more complex and interconnected, and there is no putting that horse back in the barn, even if it made sense to do so (and if it made sense, supply chains wouldn’t be what they are in the first place).

Complexity

Just how impossibly hard it is to try and determine what parts of global trade and production are good for America versus bad, and how arbitrary any line drawn between “American made” and “foreign made” will end up being?

1) 10 million cars are manufactured in the US every year. Some by US companies, some by foreign companies (with labor employed here, but higher-paying white-collar jobs mainly in their home countries), and as much as half of what goes into these US-made cars comes from somewhere else. Is this good or bad for the US?

2) US and foreign car companies manufacture tens of millions of cars in dozens of other countries. The labor is local, but (for the US companies) the management jobs are here, and both US and foreign makers use components imported from the US ($93.5 billion worth in 2024). Is this good or bad for the US?

And this is just for the auto sector. Suffice it to say, a material portion of what goes into US-manufactured goods (not to mention the facilities in which they are manufactured) comes from somewhere else, and a material share of what goes into foreign-manufactured goods comes from the US as well.

Self-Sufficient Market Efficiencies

Furthermore, even when we are self-sufficient in an industry (i.e., U.S. supply matches U.S. demand), we’re still better off with freely moving goods, as unencumbered trade flows create huge cost and logistical efficiencies; and in the case of fully (or nearly) self-sufficient sectors, we’d be throwing away those advantages with quite literally no offsetting gain.

For example, the US produces nearly as much steel as we consume (speaking of bipartisan political boogeymen that are entirely fabricated, I’ll bet even our highly educated reader base didn’t know that one); however, it’s not as if every ton of steel produced in the U.S. is consumed in the U.S., nor can the same be said of the iron ore or scrap steel that go into making steel (both of which are also fully self-sufficient sectors).

In 2024, we produced 79.5mm tons of steel and consumed 86.1mm tons. Does that mean we imported 6.6mm tons? No, we imported 26mm tons, but we also exported 10 million tons (any remainder is due to changes in inventory levels). Same for scrap steel, where we consumed 63mm tons, imported 158mm tons and exported 392mm tons.

While perhaps this sounds contradictory to someone who isn’t buried in this stuff every day, we promise you, this is just smart, free-market capitalism at its highly efficient finest.

If we have matching tonnages of scrap steel supply on the west coast and demand on the east coast, but each party can get a better price by selling to Asia and buying from Europe, respectively, would we really want them to trade with each other, when this serves only to increase the cost for themselves and everyone up the production chain from them?

Does it make more sense to sell steel produced in Texas to an auto plant 275 miles away in Monterrey or ship it 1,500 miles to an auto plant in Detroit, when that Detroit plant could get its steel from a producer 250 miles away in Toronto? You end up with the same net-zero trade balance, but at a much lower cost to everyone involved.

Price

Aggregate Demand

Economists talk about how supply and demand react to changes in price in terms of “elasticity”, with “nice to have” goods and services being more elastic (e.g., if Disney World raises ticket prices 30%, they’ll see a substantial drop in visits) and essential goods being highly inelastic (e.g., it’s hard to stop buying groceries, regardless of price hikes). Incidentally, this is also why inflation-griping is always about the price of things like eggs and not the price of things like Disney World tickets.

Well, the literal purpose of tariffs is to raise prices on goods, and while the degree to which higher prices will reduce demand will vary, no product is completely inelastic, and you will see a reduction in aggregate demand for every single tariffed product.

This means that even if tariffs serve to make marginal, less efficient domestic production viable, it will come with an offsetting reduction in demand, and there is a level at which tariffs will end up cutting into demand for the domestic production we already have, never mind anything new.

Household Costs

As we noted above, standard of living is a combination of how much one makes and what that income can buy. Even if tariffs raised incomes in the aggregate, they will both reduce the items consumers are able to buy and make the things they continue to buy more expensive, so the average American is likely to break even at best.

Choice

Sticking with the auto sector example, last year, Americans bought ~371,000 BMWs. BMW actually produced more cars than this (~396,000) in its South Carolina factory, but the US also imported ~200,000 BMWs while exporting 225,000. Why? Because BMW only makes SUVs in this facility and Americans also want to buy BMW sedans. As with the steel market example above, net trade here is already balanced (actually a small surplus), so the disruption that taxing the import leg would cause here doesn’t even have a theoretical upside, never mind a practical one.

This is obviously less pressing than the other impacts of tariffs, but it’s not nothing.

Efficiency

Even if broad tariffs work as advertised, and we build a bunch of new production capacity, and somehow there is no demand impact, this would still be bad for US manufacturing in the long run.

Yes, you may open the door for marginal, lower-efficiency production capacity to come online in the short-term, but in medium-term, you’ll inevitably invite the current, high-efficiency producers to become complacent and lose that efficiency edge (it’s just basic human nature; if you don’t need to scratch and claw for every little edge, you won’t). So in the longer term, this will not only make us uncompetitive globally and thereby reduce exports (not ideal if your goal is to balance trade), but you’ll also eventually make the whole sector dependent on tariffs (versus just the marginal producers they were meant to help in the first place).

Last thing on this – did we just waste a couple thousand words on a policy that’s looking like it may be entirely scrapped in the next month or two? Possibly, but the 10% across-the-board tariff increases remain in place, and we’re still north of 100% on Chinese goods. We would additionally argue that it’s still useful to examine all of this regardless of where we eventually land, lest we make the same mistake again in the future.

Even more concerning, we also think that going down this road in the first place, and perhaps more importantly, the clumsy implementation and subsequent on-again, off-again whiplash is likely to cause longer-term damage regardless of where we end up once the dust settles (if it settles?).

Why do we believe this to be the case?

Why has America Attracted So Much Investment for So Long?

This part is pretty simple. America has been the best place on the planet to invest for the better part of a century (if not longer) for two primary reasons:

1) Consistent, free-market economic policies.

2) The rule of law.

Do not be fooled by the snap reactions in the stock markets to every bit of tariff-on, tariff-off news. While it’s considerably easier to try and re-price risk in highly liquid public equity markets, it’s extremely difficult to do so when making strategic, capital investment decisions. For CEOs and financiers, these decisions are based on multiyear assessments of opportunity and risk, and the more uncertainty in these assessments, the less the assessors will be willing to invest.

We’re already running way too long here and still need to hit the venture market impacts, but if you’re looking for evidence that the damage done to both of these pillars of American economic success has badly shaken the investor class (both here and abroad) just look at what’s happened to treasuries and the dollar. Unlike equity investors, bond and currency traders generally do not change their long/short biases based on what they believe are short-term disruptions, and they certainly do not make buy/sell decisions based on political biases.

If this all sounds troubling to you, it should.

Venture Impact

On the one hand, we have to think that the current level of upheaval and overall uncertainty is a negative for everyone to one degree or another, and it also seems that we may be headed for a recession sooner rather than later.

On the other hand:

1) Startup and VC markets in general (especially early-stage VC) are about as close to immune as one can get to short-term volatility. We have long investment time horizons (so long in fact, that even the potential tail on this mess should be sufficiently negligible by the time companies we invest in today are fully scaled) and it would take something a lot worse than even a severe recession to materially disrupt the steady upward march of technological innovation.

2) We were overdue for a recession anyway. It’s been 17 years since we had a real one (we’re not counting the pandemic shock, which was kind of its own animal), which is an exceptionally long period by historical standards. So, if it comes sooner than it otherwise would have, it’s not the biggest deal, at least for us.

3) Assuming that at some point here, we come to our collective senses on the right way to optimize the US economy (manufacturing and otherwise), there is no scenario, at least that we see, where technological innovation is not the biggest piece of that optimization.

4) Specific to C2V, as you may recall from last month’s newsletter, a core component of our investment thesis is our postulate that our companies, by virtue of their productivity-enhancing ROI (i.e., allowing customers to do more with less) should be relatively recession-resistant (even more so if you throw higher input prices in the mix as well)

5) A corollary to this for the venture market as a whole is the potential impact on exits and liquidity. Certainly, any recession and accompanying bear market will be a negative for IPOs, but while they tend to get the most press, they generally make up a very small portion of overall venture exits (7% over the past 10 years).

Furthermore, we’ve witnessed what we believe to be a tremendous amount of pent up M&A and PE buyout demand that is not finding enough supply, as evidenced by exit values in both markets going trough the roof in recent quarters (including Q1 of this year), so even if this demand comes down in a recession, there should still be plenty of demand for that limited supply (which we don’t see becoming much less limited anytime soon).

We’ll see how this all shakes out in the coming months, but until then, chin up; we’ll get through this.

C2 Ventures is excited to announce our investment in EDEN, a Seattle-based startup transforming the $400B home services market. EDEN enables HVAC and home-service contractors to close more deals with instant quotes, transparent pricing, and deep home-specific insights, addressing an outdated sales process with a digital-first approach.

Launched in 2024, EDEN has already driven $9M+ in installation sales through its Instant Quote platform, powered by a proprietary building-stock database. Contractors benefit from precision—load calculations, equipment matching, rebate transparency, and dramatically higher conversion rates.

In addition to really nailing the “dirty” and “dull” parts of the thesis, this sector is huge and about as antiquated as they come (i.e., nearly unlimited green space for new software). We believe EDEN is well-positioned to become the go-to customer conversion funnel for contractors across the country.

NYC in Spring Never Misses

Chris had a great week in NYC; always a special time to be in the city. He caught up with some of our favorite founders and a stellar crew of longtime friends and top-tier VCs at the ERA demo day. The lineup included:

As always, good conversations and sharp thinkers.

NYC delivered.

Cive Robotics Trains on CivDot+ with Spray Paint

Last month, Civ Robotics hit the field with the team at Cupertino Electric, Inc. to demo and train on their latest tech, CivDot+, with spray paint. The result? A masterclass in precision, productivity, and on-the-ground impact.

From the first dot to full deployment, the CEI crew picked it up fast and started transforming their workflow on the spot.

Magellan AI Pokes Fun at Podcast Naming Trends with April Fools' Rebrand to "Podgellan AI"

In the spirit of April Fools' Day, Magellan AI, known for leading the way in podcast advertising intelligence, jokingly announced a "rebrand" to Podgellan AI. The playful stunt pokes fun at the industry’s love for all things "pod," while reinforcing Magellan’s commitment to the podcasting space. No need to update your bookmarks—their powerful suite of tools for measurement, attribution, and competitive insights remains the same, and so does the name.

The joke was timed with major industry moments like Podcast Movement Evolutions and their sponsorship of Podnews, showing Magellan AI is not just serious about podcasting—they're also serious about having a little fun.

Paladin's CEO Kristen Sonday On Streamlining Pro Bono

In a recent interview with Law360 Pulse, Kristen Sonday, co-founder and CEO of Paladin, discusses how the platform is transforming pro bono legal work. By leveraging technology, Paladin aims to make it easier for legal professionals to find and engage in volunteer opportunities, thereby addressing the justice gap. Sonday shares insights into the platform's origins, its mission to increase access to justice, and the impact it's making in the legal community.

Phalanx Takes the Stage at Tom Tom Festival

“Big moment for the team! 🎉 Phalanx was just named one of Virginia’s most innovative startups. Grateful to be building something meaningful with people I admire.”

Phalanx has been selected to participate in the Virginia’s Most Innovative Startups showcase at the 13th Annual Tom Tom Festival, as part of the #EVOLVEConference Technology Track, under the leadership of CEO Ian Garrett.

Tarform CEO Taras Kravtchouk recently joined CNN to discuss the challenges of running a clean tech startup in today’s unpredictable policy environment.

From navigating global supply chains to managing the added complexity of tariffs, building sustainable vehicles is no small feat.

New York’s Upcoming Commercial Waste Zones Policy

Our portfolio company WATS is helping commercial real estate owners prepare for New York City's upcoming Commercial Waste Zones (CWZ) policy. In a new case study, WATS demonstrates how their waste operations platform enabled a major client to analyze 12 months of data, identify significant savings, and stay ahead of new compliance requirements. Their insights revealed a path to cutting waste costs by 27% per site, proving that more innovative waste management isn't just better for the environment, it's better for the bottom line.