C2V January Notes From The Trenches

Welcome, friends, and a very happy New Year to you all! We know that long winter break (where, over a week or two, you gradually went from thrilled to be reunited with family, to feeling a little claustrophobic, to glad you live in a different state) left you longing for some much-needed C2V in your lives, and we couldn’t be happier to deliver.

We thought we’d kick off the year with a deeper look at one of our annual predictions from last month’s newsletter…

“At least one high-profile late-stage VC shocks the industry with the announcement that it is shuttering operations after having to realize massive losses on its 2020/2021 vintage fund(s).”

… by posing a question that’s been on our minds for several years now:

Should Late-Stage Mega Funds Exist at All?

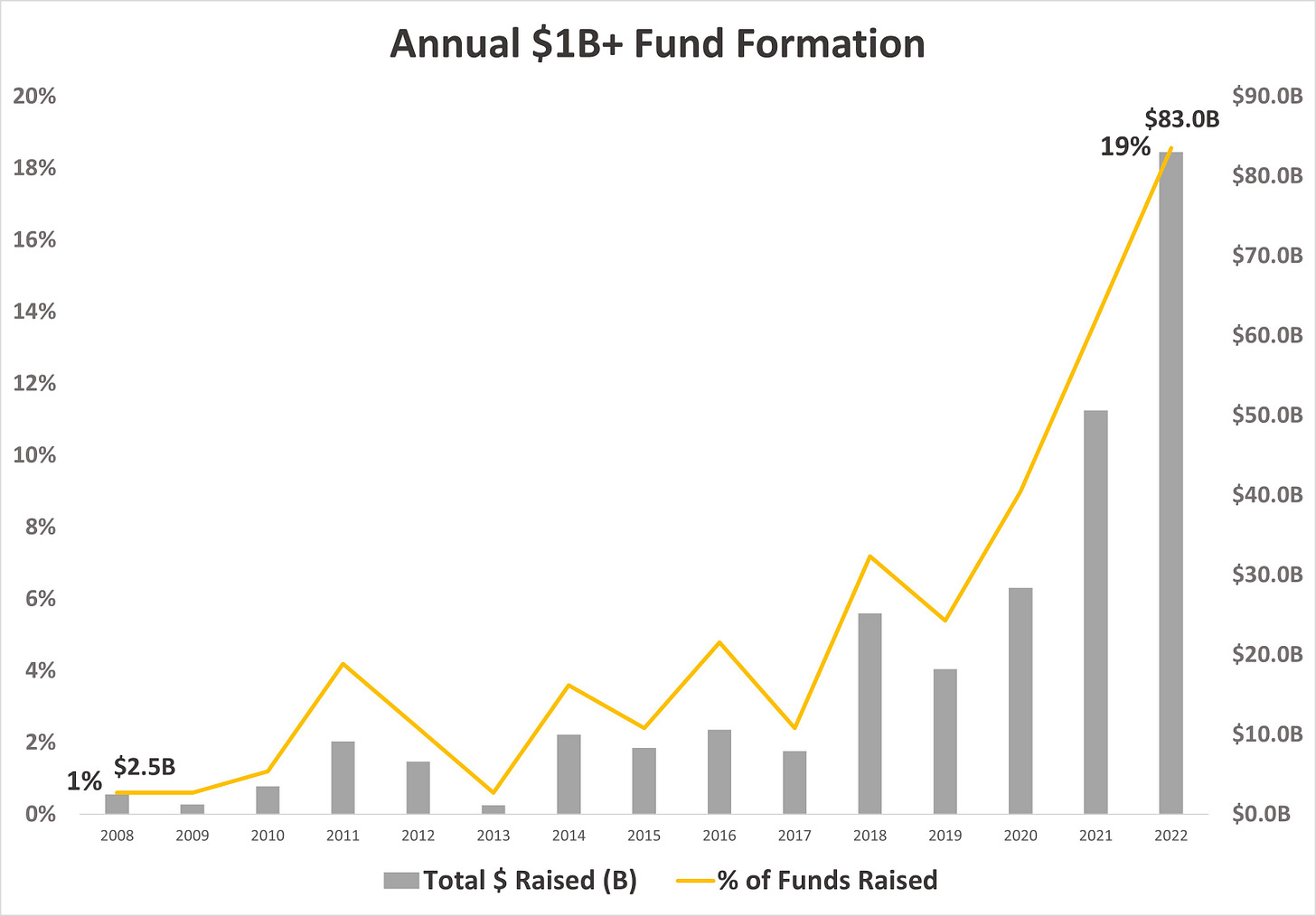

Venture capital is an industry that made its bones with small funds investing in very early tech startups. Even as recently as 15 years ago, $1 billion-plus mega-funds were nothing more than a rare novelty, but in recent years these funds have exploded in numbers.

Per the Pitchbook-NVCA Venture Monitor, $1 billion-plus venture funds went from 1% of all funds raised in 2008 to as high as 19% in 2022, and $500 million-plus funds went from 2% to 44% over the same period (by count, not assets, though those were up about 40x, as these funds have also gotten bigger over time). To be clear, this isn’t a question of why gigantic venture funds exist (if nothing else, it’s hard for managers to turn away LP money, especially when that money pays 2% annual fees); the question is, should they exist?

Unless we’re missing something, it’s hard to develop a compelling case for “yes” for two primary reasons:

1) It’s Really Hard to Make the Math Work

With the caveat that fund strategies will vary and we have to do some inferring (based on the information that is public), we can at least ballpark the numbers by applying a fund construction strategy similar to our own to a $2 billion fund (slightly smaller than the average mega-fund raised in the past 3 years). In an effort to be as generous as possible, we made some tweaks to the first check/follow-on reserve split (70/30 vs. our 50/50), a bump in companies per fund to 30 from our 20 (we could maybe go higher here, but much more and you’re just building the world’s most expensive index fund), and an estimated follow-on rate of 80% (24 of 30 companies) vs. our target of 60% (as you should theoretically have a higher hit rate at Series C/D vs Seed).

This results in the following assumptions:

An average first check of $36.9 million, targeting 10% ownership

Two pro rata follow-on investments, totaling $19.8mm

These are obviously substantially larger checks than even funds investing only a couple of rounds earlier (e.g., 3-5x a typical Series A fund), and the natural reaction might be to see these huge numbers as an opportunity, but in practice, they end up being much more of a constraint (and a severe one at that).

According to Carta data, the average dilution in Series C and D rounds is 12.6% and 10.3%, respectively (and dilution tends to flatten out or decrease the further you get into the alphabet). Even if we assume our mega fund accounts for 75% of the investment in its initial funding rounds (and sticks to pro rata shares of subsequent rounds), that implies an all-in average entry valuation around $500 million per company.

To put this in context, based on our median portfolio position, we return an entire fund with a single exit in the $450mm - 500mm range. In other words, if we sold any one of the twenty companies in any of our funds into a $2B mega-funds’ initial funding round, it would return the entirety of our LPs’ principal (plus a small profit).

But wait, you say, exit values are rising as well. That’s true, $1 billion-plus exits are much more common today. In fact, we suggested retiring the term “unicorn” and rebranding $1B+ startups in this space nearly three years ago for that very reason, but they’re still not remotely keeping pace with the increase in entry points.

According to Crunchbase, there were 340 exits of more than $1 billion between the beginning of 2020 and Q3 of 2023, an average of 86 per year (at a median exit value of $2 billion). That sounds like a lot until you consider that even if you only look at $1 billion-plus funds raised 5 - 7 years prior to this period (i.e., those whose companies are in the prime exit range; also a period when there were far fewer mega-funds than we have today) and assuming 30 companies per mega-fund, that’s an average annual pool of 730 companies just from this subset of funds (meaning only 12% exited at $1 billion or more).

Furthermore, 80% of these uni-exits (exit-corns?) raised less than $500 million in total venture money pre-exit (so maybe one or two late-stage opportunities) and the 43% who raised less than $200 million likely bypassed late-stage venture almost entirely. This reduces the exit-corn share of late-stage holdings to 7%, in an exit market that was the largest in history by a mile (and due to the recent explosion in mega funds, that pool of exit-range companies will triple by 2026).

A 7% exit-corn rate would be great if we were talking about traditional early-stage venture, but at these entry valuations, a $2 billion fund needs closer to a 50% exit-corn rate (including at least a couple 11-figure wins) just to get to a low-20s net IRR.

In other words, managers need to execute nearly flawlessly, and land a little timing luck, just to generate what would be middle-of-the-road returns for an early-stage fund (and if you’re thinking the economics of these funds can’t possibly be this bad, we must be missing something, we’d encourage you to check out Matt’s stage-by-stage breakdown of the VC returns on last year’s $10 billion Instacart IPO).

2) You’re Opting Into a Negative Selection Bias

The other conundrum we see with VC mega-funds is that the pool of companies in the market for multi-hundred-million-dollar funding rounds will always include a few truly capital-intensive, hardware/equipment-heavy businesses (e.g., Rivian, SpaceX) but the rest will almost exclusively be companies with terrible business models, particularly if you’re looking to invest in enterprise SaaS (as the vast majority of these funds are). Why? Because an enterprise SaaS business with revenues large enough to justify a mid-9 figure valuation should already be profitable (or very close to it), so any that are burning enough cash to need hundreds of millions in new capital probably shouldn’t be raising money at all; they should be shutting down.

As we noted last year in our analysis of publicly traded SaaS companies, those software companies that burn large amounts of cash despite large revenue bases generally do so due to poor gross margins, poor returns on sales & marketing spend, or (usually) both. While this could mean their CS and sales teams are just terribly inefficient and in need of an upgrade, it’s far more likely that their product is sufficiently subpar or undifferentiated that it’s incredibly difficult to sell, even at a price that is unsustainably low. Either way, though, these high-revenue, high-burn SaaS companies are not businesses that people should be lining up to throw money at.

Of course, we don’t have enough transparency into these private portfolios to definitively confirm that public SaaS companies are a fair representation, but:

60% of the companies in the dataset we examined were very recently venture-backed (IPOs between 2019 and 2021)

If the financials of those that are still private are materially better, why are they still private?

2a) It’s Based on a Flawed Premise to Begin With

The argument for late-stage, mega-VCs often centers around a bit about how companies like Google, or even as far back as Abobe, were forced to go public earlier than they wanted to in order to fund their growth and that this new segment would allow their successors to stay private longer. It’s a strange argument to be making, because while it may seem compelling on its surface, it completely falls apart with even a quick glance at any of these company’s financials:

In 1986, the year Adobe went public, it reported a 22% net margin on $16 million in revenue (just like Chris, Matt and everything else that grew up in the 80s, Abobe walked 8 miles to and from school every day, uphill in both directions, usually in a blizzard);

Two years before its 2004 IPO, Google reported net income of $100 million on revenues 26% lower than what recent mega-fund darling Snowflake reported in 2021, a year in which it managed to lose $544 million (Google’s net margin that year: +22.7%; Snowflake’s: -91.9%).

So the idea is that Google, Adobe, and/or their peers, if given the option, would have delayed their IPOs a couple years, just so they could be jammed with a few multi-hundred-million-dollar cash injections they didn’t need (plus the accompanying cap table dead weight), and then go public?

Maybe we’re missing something, but from where we’re sitting, it’s hard to see anything other than a very (very) expensive house of cards here.

New Investment

We’re pleased to announce our latest investment from our Pre-Seed, Tributary Fund, in mortgage-tech company, Approva, a loan administration software platform and broker-lender marketplace for the $150 billion non-prime mortgage market.

Significantly more fragmented, opaque, and antiquated than its prime counterpart, the non-prime sector presents tremendous opportunity for innovation (as well as a 12-figure TAM), but has been largely ignored during the recent wave of property- and mortgage-tech innovation. Non-prime mortgage application submissions and approvals are exceptionally slow compared to the prime market, due to a combination of disjointed, manual application, submission, and underwriting processes, and an opaque lender market that lacks any standardized approval criteria, or centralized information hub (brokers literally still call lenders one-by-one to figure out where to send each application).

Approva’s platform provides both a centralized hub connecting brokers and lenders, and tools for each to automate their end of each loan origination. Integrations with credit, payroll, and property databases allow Approva to quickly pull relevant data needed to compare borrower information to the preloaded criteria of lenders on its platform (50+ and counting), provide quotes instantly, and automatically populate and submit applications, reducing a process that currently takes an average of 17 days down to 6 minutes.

2023 proved to be a year of consistent progress for us. With 3,476 deals considered thus far, we now support a diverse group of 104 ambitious founders and help 44 portfolio companies thrive. Our 29 follow-on investments (and counting) in these companies are a product of both a selection process that has proven over many years to consistently identify good products and founders, and a willingness to double down on our best performers.

C2V Watercooler

A decade’s journey for us! It all started after Chris’s stint as Appsavvy’s CEO and co-founder. The fire of entrepreneurship was still there, but this time, his desire was to work with young, hungry tech founders.

Over the last 6 years, we have capitalized on the established C2V brand, keeping the momentum and community strong. With three funds launched and over 48 tech startups backed, C2 Ventures stands tall.

It’s no picnic being a startup ourselves, but we’re creating something special, something built to last. So here’s to C2V, the name that stuck, the brand that evolved, and the legacy we’re crafting, one startup at a time.

Portfolio News

Otis makes online heartworm prevention a reality

Otis, which provides access to veterinary care at a fraction of in-clinic cost, just launched heartworm medication. This makes them the only company prescribing heartworm preventatives for pets online. Sign up and get your 1st month of flea, tick & heartworm prevention free with code “C2V”.

Asks: Otis is looking for future partnership introductions. If you have connections to pet insurance, pet food, pet adoption/rescue, and pet services (daycare, grooming, boarding) companies, please reach out to vivian@otispet.co.

Cameras with artificial intelligence aim to enhance electric service reliability

Mounted on an Ohio Edison bucket truck, a smart camera paired with artificial intelligence (AI) silently takes thousands of high-resolution photos in northeast Ohio, identifying and geolocating utility poles. In Pennsylvania, another camera works to identify defects in poles and equipment that may need human attention in Met-Ed’s service area.

These aren’t scenes from the future. FirstEnergy and its electric companies have been exploring such innovations for the past two years with Noteworthy AI, a Connecticut-based firm that provides AI-powered cameras to help utilities evaluate the condition of their equipment.

Noteworthy AI is one of seven startups accepted into the Florida Power & Light/Nextera's Incubator

Wishing a warm welcome to the seven new startups that have been selected to join our 35 Mules program, an innovation hub designed to help early-stage startups bring their brightest ideas to life faster, smarter and at scale.

They will work on their respective ventures right here at our NextEra Energy facilities, gain access to subject-matter expertise and advanced technology solutions, and make valuable connections in the Florida business community.

Phalanx CEO and Co-Founder Ian Garrett was honored as a NVTC Tech 100

A round of applause for last week's Northern Virginia Technology Council (NVTC) Tech 100 event! Among the many outstanding companies and individuals in attendance, one shining star emerged: Phalanx CEO and Co-Founder Ian Garrett.

Ian’s selection as a NextGen Leader is a testament to his dedication to shaping the ever-evolving landscape of technology, all while drawing inspiration from the inspiring community fostered by NVTC.

Rigorous: A look into one of VT's most exciting robotics companies

Williston-based Rigorous Technology is not your typical robotics company.

Co-founded by Colin Riggs and Diane Abruzzini Riggs, the company is on a mission to build robots for small to medium-sized manufacturers, which can lack the resources to effectively manage automation internally.

Rigorous was founded in 2020 when Colin, who always wanted to start a robotics company, secured two manufacturing contracts as an independent consultant. One contract was for a slate manufacturer, the other for a research vessel tasked to find sunken warships.

Paladin Acquires Pro Bono Manager to Expand Pro Bono Reporting Capabilities

Today, two leading pro bono and access to justice innovators, Paladin and Pro Bono Net, announced Paladin’s acquisition of Pro Bono Manager. Pro Bono Manager is a robust pro bono reporting product used by many top AmLaw firms to measure the health of their pro bono programs.

The acquisition will equip pro bono teams with more data and insights, broaden Paladin’s law firm network nationwide, and expand knowledge of best practices to support the pro bono community further.

Top 10 weirdest tech innovations of 2023

If you're looking for some weird and, in some cases, bizarre technology that will blow your mind, you've come to the right place. We've compiled some of the most fascinating and futuristic gadgets that have amazed us over the past year. From a hamster ball robot that can fly and crawl to a pair of jeans that can save you from motorcycle accidents.